..

On actors: We had a few really strong actors. Michael Davis is a very strong actor, a lot of experience in improv comedy. Randy Cox is a strong actor. These were actors who played multiple roles because I could tell from their auditions that they could handle it. ![Creeporia Cast Creeporia Cast]() The thing about the girls [Camille and Kennerly Kitt] is that they were perceptive.

The thing about the girls [Camille and Kennerly Kitt] is that they were perceptive.

Some of the other actors who auditioned were horrible. Some people couldn’t even read, let alone act. So, it was a breath of fresh air when I came across these two young talents who could find the nuances in the dialogue and understand where the jokes were.

Jim Mannan is a good, strong actor. The plus to Jim is he that was also a dedicated worker. He was one of the most professional people on the set, in that he was required to be on set for a very long time and never complained. He just had a fantastic demeanor and dedication to the film.

Tristan Ross: I could tell was a very strong actor and, therefore, I felt very comfortable handing him a significant role. I am happy with what he did, but word reaches me that he is less than appreciative of having been in this film, which I think is a shame, because I think he did a good job.

When you guys originally sent me the audition tape for Mark Carter (Sammy Terry), [executive producer] Patrick [Greathouse] was trying to sell me on the idea of Mark being the male lead. I didn’t see that in Mark. What I saw in his performance was a kind of larger than life personality that would be perfect for the game show host, Blink Nightingale.

![Creepoira and Blink (Mark Carter)]()

Mark is really funny and this character needed a lot of room to expand. I couldn’t tell from the audition tape whether or not Mark had great acting chops (it turns out that he does), but I could tell that there was a comfort in front of the camera and that there was a big personality.

Patrick first started talking to me about Sammy Terry, and Pat was obviously very excited about Sammy Terry, but I didn’t grow up in Indianapolis. I didn’t have a clue who Sammy Terry was. In fact, the first time I laid eyes on Sammy Terry was when Mark was in the makeup for those extra scenes.

I didn’t originally write Sammy Terry into the script. So when I decided that Mark should play the game show host that was just based on seeing the audition tape. It was a perfect fit. That is an example of casting close to a kind of personality and ending up richly rewarded. Mark so completely threw himself into that role that I think he is one of the high points of the film.

![creeporia twins and sammy terry]()

John Claeys (Mad Genius Professor) is an interesting situation. In the bowels of his living situation there; that building, down in the basement where he works his art director magic, one night he shot a video audition as the Professor. He so perfectly nailed it that I didn’t care whether he could act or not.

Quite frankly, I don’t think John is a very strong actor. I think he would have to agree with that. But, he saw himself playing that character and his audition tape convinced me that, yes, there was so much in that character that was him that it would be worth casting.

Now, I will say this: It was difficult with John because he isn’t particularly good at memorizing lines. I don’t think he got through a single run of his lines without screwing it up once. But, I come from the world of post-production, so I think like an editor. This, by the way, saved us.

![Creeporia and the Professor]()

I tend to think in terms of bits of film that I know I am going to use in a certain way down the line. I knew how I could edit John. I knew when I had enough of a take to use. By a combination of John really throwing himself into the role, making a lot of mistakes, but still really throwing himself completely into the role, and then me knowing how to cut around the mistakes, I think, again, that John’s performance is one of the strongest in the film.

On working with Alfred Eaker (as an actor in a cameo): Alfred was impossible. The dressing room wasn’t warm enough, there weren’t enough people catering to his needs. You were just a total prima donna (laughter).

First of all, we shot you twice. I had to come back to Indianapolis to re-shoot you, which actually had nothing to do with you. You had just had surgery. You were like at death’s door. We got you out of your hospital bed, we got you out of your death-bed and you delivered a brilliant performance, which, of course, will be your last (laughter). You were fine to work with.

This is how much I appreciate what you did: You guys opened the movie. You have one of the first lines of the movie. Of the first ten lines, about five of them are yours. I am very happy with the opening, especially after we re-shot it. I should point out that the re-shoot had nothing to do with the actors and everything to do with a particular cameraman from L.A., whom we had hired for just a couple of days.

![CREEPORIA. JOHN SEMPER AND STAN LEE]()

On working with Executive Producer Patrick Greathouse: Here is one of the things that makes Pat one of my favorite producers and puts him in the same league as Jim Henson and Stan Lee: the best producer on the planet is the guy who basically is just going to leave you alone, let you do your thing, and support you every step of the way.

The only two other producers that I have worked for, who did that for me, were Stan Lee and Jim Henson. In my universe that puts Pat in an elite group. So, whatever shortcomings he might have exhibited, he is up at the top of my list. He continues to be supportive. I had a wonderful time working with Pat and I think the product reflects that. If I had any difficulty working with Pat, then it wouldn’t have been easy for me to work on the project and the project might not have gotten finished.

On the two local cameramen and a cameraman from L.A: We needed a cameraman for a couple of days because our regular cameraman, JD Brenton, wasn’t available for those days. Someone recommended a hotshot cameraman from L.A. I did not know him.

The problem with out here (L.A.) is that, yes there are a lot of talented people, but there are also a lot of posers; people who come out here to reinvent themselves as something they really aren’t, they’re pretending to be specialists.

The reason that happens is because L.A. is a place where you really can lie your way to the top. There have been a number of situations where writers have been found to have lied on their resumes; they have gotten elevated to a high position in the Writers Guild, or whatever Guild, and then one day somebody starts pouring through their bio and realizes that a good percentage of it is made-up. There is a lot of that out here.

Basically, you are what you tell people you are. So, you get a lot of sociopaths who succeed very well out here. That breeds more sociopathic behavior. People look at that and see that it succeeds. Some of the top people out here, with names that you would know, are horrible sociopaths. They’re liars, cheaters, and that’s the way things are out here.

![Creeporia. John Semper and Nosferatu]()

The thing that I felt about that cameraman (from L.A.); he was kind of legend in his own mind and when it came to the practical business of doing his job, and doing it well, and making people comfortable—he wasn’t good at that. It was bruising his ego that I was in charge and he wasn’t, which is something a director should never have to deal when dealing with a cameraman. It was bruising his ego that this was not his film and he was very obvious about it. He made me very uncomfortable, he made the actors uncomfortable. He was parading around like he was in charge, which caused extra work for a number of people, and then the bottom line; with all this grandstanding and pomposity, he wasn’t a very good cameraman.

He was so busy parading around and pretending to be something that he forgot to actually be it. He didn’t really understand the camera very well. He made a number of mistakes that created problems for me in editing. That’s why I had to come back to Indy and re-shoot, to fix his mistakes.

That’s what I expect from L.A. and that’s why I wasn’t too excited about bringing L.A. people to Indianapolis. I figured in Indianapolis you would have good, talented people who are free of this kind of attitude and that’s exactly what happened.

Our primary cameraman JD Brenton was fantastic to work with. He was constantly suggesting things, never got in my way, always supportive of what I was trying to accomplish. If he suggested something and I didn’t like it, he didn’t take it personally. There was no ego involved. He also happened to be really talented and I might point out that when we started he didn’t really know that particular camera we were using either. Even with that, he learned it very quickly. He adapted to the situation and he ended up being a tremendous help.

J.Ross Eaker also did a fantastic job. At first he wasn’t going to work on the film. You talked him into it. He came in, showed no ego. He worked long hours without complaint. Again, this is why I did not want to cast out of L.A.

The cameraman from L.A. lived up to all my worst nightmares. The Indianapolis people were good, solid, get the job done.

You have to understand, when I arrived in Indy, I hit the ground running. I was dealing with jet lag. Pat, in his zeal, had scheduled the first shoot for 5:00 a.m because we had to be at this building at six in the morning. Now that was 2:00 a.m my time. So I had to do a lot of the early production just flat-out being dead tired. So it was very important to me that people be helpful, and not be a hindrance.

![Creeporia and cast!]()

All the Indy people; you, Pat, Ross, JD, everybody stepped in and made my adjustment to the new time zone much easier to deal with. I think that blue-collar attitude, which the Twins (from Chicago) also had, just handles reality better. It’s a better work ethic.

In L.A. people get spoiled. They get paid way too much money to do far too little. You get rewarded for being a diva and parading around as a character version of yourself; all the things that cameraman brought to the table, whereas I got surrounded by a hardworking group in Indy. It was cold in that building, yet nobody bitched, nobody whined. This required a tremendous amount of dedication. The girls had that in spades. A lot of times, by the evening (because we shot all day) the girls propped me up. They would remind me of things that I had forgotten to shoot. They always knew their lines, were spot on with their acting. They were a Godsend.The whole production was blessed in a way. Everything fit very nicely (except for that L.A. cameraman). There was no negative energy.

![CREEPORIA. DON TRENT WORKING HIS MAGIC]()

On the make-up artists: I think the make-up people worked harder than any of us. By the end of the production they were really tired of me because they worked harder than they expected to. There was a little bit of grumbling in the make-up room, but very little. Don Trent is a master at his craft. Don, Phil Yeary, Jen Ring, Nicole Fernandez; they were the unsung heroes.

![Creeporia meets Wolfgang]()

On the Wolfman: The Wolfman make-up was the most elaborate make-up. There is this phenomenon that kicks in when you’re an actor and you have to wear make-up like that: You start to feel claustrophobic.

Jim Carrey, when he did the Grinch, they had to hire a person to be his companion. Because, you tend to feel completely removed from everything that’s going on around you when you are in a costume like that for hours. We didn’t have the luxury of being able to treat our actors that way.

Randy Cox, who was originally supposed to be the Werewolf, came to me on the one day that he was wearing that make-up, he was fanning himself with his hand, and going: “I don’t think I… this make-up, this make-up, I don’t know if I can…” He was really kind of out of it. I was busy because that’s the day we were shooting at Miss Betty’s, so I was all over the place. We had been shooting all day. Then at night, we had the big restaurant scene with all the extras, so I couldn’t pay attention to him. After that day, he went away and never came back. I don’t hold that against him.

Fortunately, and this is another example of how this production was blessed, the guy who [choreographer] Melanie [Baker-Futorian] had found to play the werewolf in the dance, also wanted to play the werewolf in the movie. When she found out we had lost our werewolf she said: “How about Drew?” We brought Drew [Andrew S. Phillips] in. He was young, he was energetic and I know that make-up drove him crazy too, but he could handle it. He also had a dancer’s body. He brought all this wonderful dancer’s body language into this character that enhanced the make-up.

Even though Randy couldn’t continue, because of the make-up, that actually worked out well because we got someone who was better suited to playing that character.

On John Semper as the voices of Bonaparte, Batty, and Maurice: That had nothing to do with vanity. When I was doing the web series, I didn’t want to have to round-up actors. So, I just decided that I would do the voices of Creeporia’s characters who live in the crypt with her, and I knew that I could.

Lord knows I have been around enough voice-over people, I’ve been in a lot of voice-over recording sessions, I’ve seen Mel Blanc perform on several occasions, including one of my scripts for The Jetsons. So, I know how to do it.

![Creeporia in a pickle]()

On the Production: Pat, bless his heart, is one of those guys who, and this is what I love about him, he sees no limits. If you said to him, “Pat, I just bought an airplane, and we need to get it into this building,” Pat’s a guy who will go,” well we could remove the roof and we could just take the building wall down, and we could get a 4 wheeler to drag the airplane.” It’s amazing the stuff that he’s ready to tackle.

So, the big picture: Pat is phenomenal. The small picture, I think, tends to elude Pat a little bit. I don’t think he really understood what would be required on a day-to-day basis as far as the production was concerned. Originally we were going to shoot in summer. I had a feeling that he wasn’t ready yet, even though he was painting things, moving things, removing walls, putting up dividers, doing all this amazing stuff, I just had a feeling, from a practical point of view, that he wasn’t really ready.

So, it got put off until November. Delays are, sometimes, really a Godsend. We’re having delays now in getting this film done. I know that it disappoints people, but the fact of the matter is that every time this project has been delayed, it ends up benefiting the project.

Had we made this film in the summer, we would not have had enough money. But, because it got delayed until November, then all of a sudden, the financial picture changed and we were able to spend more money on the film, which made it better. I think the same thing is going to happen with release of the film. It’s disappointing in this era of instant gratification that it wasn’t ready within a month after we shot it. But, as far as distribution is concerned, I think the delay is going to have this film ready at exactly the right time, and I stand by that. The beginning of next year is exactly the time for this film to be getting out to the public.

The challenge for me is that sets would literally be ready the day we were supposed to shoot in them. I had no preparation in terms of blocking, we were changing the schedule on an hourly basis. Things got so out of whack that at one point I said, “Let’s just stop. Let’s not do anything. Let’s all get a good night’s sleep, let’s all sleep in the next day, let’s just gather our wits about us.”

There were a couple of times that had to happen. It was a real trial by fire. Because literally, I would walk into a set and see what Creeporia’s living room was going to look like. Let’s put the camera over here and I would make it up on the spot, how I wanted to block things out. And, again, that’s where my post-production experience came in handy. I couldn’t do any elaborate camera moves. I’m not really big into elaborate camera moves anyway.

![Creeporia Kitt Twins]()

All this steadycam stuff that you see on TV drives me crazy. It would have made our production even more complicated than it already was. When I look at some of the scenes and you see Creeporia’s interior; it all looks very well put together, and orderly, and very much the environment it is supposed to be. I know that literally inches outside of the edge of the frame there was dirt and cables, crates; just chaos! But, we would somehow be able to get the camera view just perfect.

To give you a really great example of the lack of preparation and the amount of luck that we had: Melanie was rehearsing the dancers for the dance number. I had no idea where we were going to shoot the big dance number. It was supposed to be on a Broadway-like stage. I had no idea where we were going to shoot that.

As we got closer and closer to shooting I thought we would have to knock down some of the walls of our sets and just shoot it here in the sound stage. But even then, even knocking out walls, there just wasn’t going to be enough room and the crappy carpet was on the floor and it really looked awful. How are people going to dance on this? I had no idea.

![Creeporia twins Camille & Kennerly Kitt]()

The weekend rolls around and we were supposed to be shooting the dance number the next week. Pat calls me and says: “John Claeys called and he wants us to come over, look at this house, and look at the stuff he’s got hanging on his walls and everything.

So the girls, their mother, and I pile into the car and we go to John Claeys’s building. We are looking at this amazing display of “Claeysiana” that he as all over the place. It’s like stepping inside of his brain, which is an amazing experience; very talented guy. And then he says “I want to show you where we’re going to shoot the laboratory scene. It’s down in the basement.” He lives in a building that is a very old building, and he’s refurbishing it for the guy who owns it.

![Creeporia Twins Camille, Kennerly]()

As we’re walking from his apartment to the basement, he walks us across this balcony, I look down and I see this theater. I asked about it and he says, “Oh, this building used to have a theater in it, we’re refurbishing it, and we still have events here.”

It’s like a little Broadway theater. I turn to Pat and I say,”Why didn’t you tell me this was here? This is exactly where we need to shoot the musical number! Why don’t you see if you can get it?” So, he talks to the guy and, again, this is the beauty of Pat: this is what we need, and Pat says “OK, let me see if I can get it for you.” He did, he was able to rent it for one day and literally days before we’re scheduled to shoot the dance number, I had the theater. But, that’s how this whole production went! But, when you see the film, it will look like we rented this Broadway theater, just as if we had planned it months ago!

![Creeporia: Elaine in basement lab Creeporia: Elaine in basement lab]() Elaine Sarah Miles was somebody I knew prior to writing the script, so when I wrote the script, I knew that I wanted her in it to sing a song.

Elaine Sarah Miles was somebody I knew prior to writing the script, so when I wrote the script, I knew that I wanted her in it to sing a song.

I am a big musical fan. People make these kinds of low-budget films, but they never put music in it, they never put musical numbers. So I am going to throw everyone out of whack and put a musical number in it.

Elaine and John Chiodini offered to write a song. I like to throw people off-kilter. I thought if we make this low-budget film and there’s this big MGM musical number in the middle of it, everyone’s going to go: “Oh, damn, I wasn’t expecting that!”

I’ve known Melanie Baker-Futorian for many decades and I asked her if she would do the choreography and she said: “No!” She didn’t think she could it, but I convinced her. Her issue was leaving behind the stuff she was doing in New York, and this was an unknown quantity. But, this is the way Mel does things and I love it; she throws herself into things 100 %.

As a sweetener, I threw in the business of her playing Nikki Finkenstein. She was excited about that. While she was there in New York, she choreographed the whole number and sent it to me.

![creeporia 3]()

Before she even came out, Lynn Herrick, the head of the Dance Refinery in Indianapolis, went to New York, met Melanie, and so by the time Melanie came to Indy, she was old friends with Lynn, fit right into the dance studio, and immediately started working with the dancers. That’s the kind of work ethic Melanie has.

The main number she did all herself. I made a couple of suggestions for the “We’re Cowboys” number, which Melanie choreographed in Indy. She incorporated my suggestions, refined her choreography, and it worked out really well.

Elaine and Melanie brought in a tremendous wealth of talent. Elaine was one of the few people I brought in from L.A., but that’s because I knew Elaine very well.

The other person I brought in from L.A. was make-up artist Rachel Halsey. I knew she was brilliant at make-up. But, again, I had to convince her. Getting people to get on an airplane and fly out to Indianapolis is not the easiest thing to do. She agreed to come in for a few days and teach the girls their make-up. And, again, we couldn’t have gotten through this without Rachel’s talents. Because you’re staring at these faces throughout the entire film. Creeporia is practically in every scene and she has to look spectacular or else we’re not going to want to be with her. Rachel took those cute little freshly-scrubbed faces and turned them into something really gorgeous and sexy and beautiful. Rachel’s contribution was phenomenal.

![CREEPORIA. TODD M. COE CHASE SEQUENCE. III]()

On Post-production: I always knew I would have animation in the film because, again, it’s something people wouldn’t expect and it would be a cost-effective way to do something fun and unusual. It has nothing to do with the fact that I come from the world of animation. People are going to say, “Oh, he does cartoons, that’s why there’s animation in the film.” That’s not true. The reality is there are things that I wanted to have happen in this film that we couldn’t afford.

One of those things is chase sequences. Every comedy movie should have a good chase sequence. So, the bottom line is that every time we had a chase sequence, that was going to be animated. Once I commit to using animation, it opens up to other things. I always knew I was going to have an introduction, a kind of back story that would open that movie and that would be animated.

![Creeporia . Todd M. Coe chase sequence]()

James Sanders, myself, and Todd M. Coe were the three animators. Again, timing. You introduced me to Todd Coe and I made him my chase sequence guy. Todd animated the chase sequences.

Then, an old friend of mine called me out of the clear blue from Boston and wanted me to meet this young animator. People do this all the time; ask me to meet someone who is trying to get their career started and give them advice. I always say yes. I know how important that was when I first arrived in this town.

![Creeporia . Todd M. Coe chase sequence . WITH CANNIBAL HECTOR]()

One of the first people who took me under their wing was Walter Lantz, the creator of Woody Woodpecker. When you are driving around the Valley with Walter Lantz, who arrived here in 1925, and he’s showing you the Valley from his perspective, you can’t beat that! It’s an education you can’t buy. So I always do that when people call me.

This old friend of mine called me, his name was Arnie, and he asked me to talk to this young guy. I arranged lunch and met this young, black animator named James Sanders. We hit it off really well and I brought him into the film. That opened up possibilities for me. James handled some new stuff I thought up, including a Creeporia flashback scene. So, I got two brilliant animators due to timing.

I wanted to have a fairly elaborate animated opening. I tackled the whole opening credit sequence myself. I wanted to do a credit sequence like the Pink Panther where it lasts a long time and revolves around animated characters doing interesting things that are very much thematically related to what goes on in the movie. The opening is huge, like a short film in and of itself. I am also animating the big, climactic scene at the end.

![Creeporia double take]()

I gave Todd Coe a lot of leeway. I let him come up with stuff on his own. Again, it’s similar to the way guys like Henson and Stan Lee were with me: this is what I absolutely need. Now, how you execute it, is up to you.

Todd came up with designs, ran them past me, they were all quite brilliant. He did it his way then I gave him notes as to how I needed to have it fixed and changed. I try to be a good producer because if something doesn’t work, I will tell you what I want instead. Lousy producers are guys that bark “Oh, I don’t like that! I want something better.” I have worked for those guys.

Todd’s wife, Ally, turned out to be a Godsend because she understood Adobe After Effects. I had a whole bunch of things I needed done in After Effects and she did them. They were a dynamic duo for me.

I got James set up with the exact same software Todd was using and he turned out to be fantastic to work with. They were all nice, no egos.

![Creeporia. On the set with John and cast]()

On “Creeporia” as a series: I had no idea what this film was going to look like, what the sets were going to look like, what the acting was going to be like, etc. So it was very hard for me to say what this was going to be.For lack of a better example, I called it a movie.

![Creeporia drives!]()

We were shooting a feature-length script. When I wrote the script, it was long. I always write long. Then, when the twins were going to be in it, I wrote even more to take advantage of the fact that I had twins. So, there’s a whole sequence that I added while taking nothing out. I knew going into this that it was going to be long. Doing the animation added even more, with sequences telling the back story of Creeporia. In turning the opening into an animated sequence it got long, the chase sequences added length.

There’s a certain expectation that people have when you say something’s a movie. They’re expecting something that costs millions of dollars. We didn’t have millions of dollar and, simultaneously, we had something a lot longer than 90 minutes. So I always knew I was going to wait. It would tell me what it was, not me telling it what it was.

When it all got put together, I didn’t see million dollar movie quality, but it is excellent TV quality; far better than much that is on the air. So, it’s not a movie, it’s a TV show, and the definition that popped in my head was comedy horror soap opera.

![Creeporia pic]()

If you say soap opera people expect a certain quality. We exceed that. Your criticism of what you see in a movie or a TV show is directly related to your expectations. If you walk into a movie house and the movie exceeds your expectations, you are going to give it a good review.

If the movie falls short of your expectations, you’re going to give it a bad review. So, I wanted people not to expect movie quality, but soap opera quality. The reality is that it’s better than soap opera quality. It’s actually a pretty damn good TV show.

Distribution is changing literally by the hour. All this video-on-demand has reached a point of maturity that makes it a very viable way for programming to be delivered. This wireless internet delivery of TV is being delivered into TVs that you actually buy. It’s all happening right now. That’s where I always wanted “Creeporia: to be delivered. We’re finishing this right when it needs to finished and when fate steps in, you just need to get out of the way and let it happen.

![creeporia5]()

On where “Creeporia” is going: I want “Creeporia” to be self-sustaining. I want to make enough money off this to roll into another project and this time everybody gets paid what they’re worth. To be able to do this again, to bring back a lot of the people who worked on it the first time; that’s my goal. I am in the middle of writing a couple of Creeporia books. I want to continue the Creeporia franchise, kept it going, so that people know and like the character.

I suppose Elvira might be something of a prototype, but I want it to be bigger and better than Elvira. I want to take Creeporia and put her in really funny movies. My idea of funny movies are the best of Mel Brooks, or Monty Python. If I could make a movie with Creeporia in it and it would resonate like Holy Grail, that is my Holy Grail.

![Creeporia_holly Larna Smith in Creeporia]() That takes me to this thorny problem of audience. I have gotten in a little bit of trouble with the girls over the issue of whether or not this movie is “family friendly.” I have had to do a lot of thinking about this. I have done hours and hours of entertainment that is family friendly. I’ve done Disney cartoons, I’ve done “Alvin and the Chipmunks,” “The Smurfs,” “Scooby Doo,” and “Jay Jay the Jet Plane.” But, this is not that. “Creeporia” was designed to be funny. My audience is the same audience that would turn toMonty Python and the Holy Grail or Life of Brian or Young Frankenstein.

That takes me to this thorny problem of audience. I have gotten in a little bit of trouble with the girls over the issue of whether or not this movie is “family friendly.” I have had to do a lot of thinking about this. I have done hours and hours of entertainment that is family friendly. I’ve done Disney cartoons, I’ve done “Alvin and the Chipmunks,” “The Smurfs,” “Scooby Doo,” and “Jay Jay the Jet Plane.” But, this is not that. “Creeporia” was designed to be funny. My audience is the same audience that would turn toMonty Python and the Holy Grail or Life of Brian or Young Frankenstein.

If I tune in on any episode of “Vampire Diaries,” that’s on regular television, I’m going to see the supernatural, bloody beheadings on regular television, watched by kids. I don’t do any of that in “Creeporia.” So I do regard “Creeporia” as being family friendly. But, that’s not my priority. My priority is to make people laugh.

![Creeporia and Nosferatu]()

On weird movies: One of the things I want to do is go out and shoot a bunch of films that are closer to the spirit of The Saragossa Manuscript (1965) or my favorite Ingmar Bergman film, The Magician (1958). I grew up on that kind of cinema.

It’s funny because I was trying to defend the trailer to the twins, and they hated the trailer. JD too, he was a little confused by the trailer. This is the burden when you are known for doing young kid shows, everybody expects you to continue doing that. But, when you look at my movie, Class Act (1992), it’s a sophomoric high school comedy.

I made the trailer for “Creepoira” and I kept trying to explain to people, it’s like Satyricon (1969). But, the first problem is nobody knows who Fellini is anymore, which is amazing to me! It’s like talking about the Bible and someone asks: “What’s that?” How can you not know Fellini?

Here I am talking to the twentysomething girls and I’m saying I wanted the trailer to be like Fellini’s Satyricon. Silence. I explained who he was and said: “Satyricon was a really bizarre film that out-Fellinied Fellini.”

When I was working in a movie theater and the trailer for Satyricon came on, everybody was blown away. We didn’t know what it was. All we knew is we had to see it. That was my goal with the “Creeporia” trailer. I only wanted to establish a couple of things. It was funny, silly, a lot of weird stuff going on, and I’m not going to tell you what the movie is about. If you want to know, you’re going to have to come and see it.

I suspect this was a huge disappointment to them because they wanted to see a trailer that told their story of their character. But, that’s not what I wanted to do.

I grew up with Fellini’s Satyricon. The trailer for Last Tango In Paris (1972) showed you a still photo of Brando, a still photo of Schneider, that fantastic saxophone music by Barbieri, and that was it. You didn’t know anything about it, you just knew you had to see it, and that’s the world I come from. Fellini, Bergman, Mario Bava, this is my nirvana. Al, you get that! You understand that!

![Creeporia and ...]()

On Future Films: I want to make smaller, quirky films, very talky, because I like dialogue. I like wordplay. I have succeeded in the world of commercial filmmaking. Now I am going to make movies that are personal, quirky, and out of my head. And I will probably never make a dime.

![Creeporia twins Camille and Kennerly]()

The Final Word: You were all great fun to work with. Pat and the girls are excellent, and I think the girls are frustrated with me right now, but I still love them. You can’t get through this business without upsetting people, but you just have to stay focused.

I had so many people upset with me when I made “Spiderman: The Animated Series.” So many detractors. Yet people are still looking at that series and people are still loving it. That’s because you put all your time, energy, and focus into the product itself and make it as good as you can make it. That’s what we did with “Creeporia.” All the other stuff will fall by the wayside.

Years from now when people are seventy or whatever, their grandkids are going to say; “Oh you were in ‘Creeporia’?” It will all make sense then. I won’t be here, but I’ll be smiling down.

*Executive producer Patrick Greathouse wished to add: “Thank you one and all.”

Patrick to send along the slasher script. Patrick did. Semper looked at it and asked Patrick’s opinion. Patrick admitted that he did not care for the script or for doing a slasher film to begin with. Semper agreed and thought that the script was something he had seen a million times. Semper asked the inevitable question: “What kind of movie do you want to make?” They both agreed on an old school monster movie, preferably a comedy horror.

Patrick to send along the slasher script. Patrick did. Semper looked at it and asked Patrick’s opinion. Patrick admitted that he did not care for the script or for doing a slasher film to begin with. Semper agreed and thought that the script was something he had seen a million times. Semper asked the inevitable question: “What kind of movie do you want to make?” They both agreed on an old school monster movie, preferably a comedy horror.

One of my assistants was a short, squat actor from the Haunt who told me: “Man, I have to play the werewolf character, Wolfgang. I am really into the werewolf culture. It is my life’s destiny to play a werewolf.” We had a few decent auditions for the werewolf part, including said assistant, but none that were particularly striking. One potential actor read for several parts, and I wanted him to read for Wolfgang. I asked the assistant to give the actor the Wolfgang sides. A short time later when the candidate took the stage, I asked him to read for the part. “Your assistant told me that I couldn’t read for Wolfgang because the part has been filled.” Scratch one assistant and any idea of a short, squat lycanthrope.

One of my assistants was a short, squat actor from the Haunt who told me: “Man, I have to play the werewolf character, Wolfgang. I am really into the werewolf culture. It is my life’s destiny to play a werewolf.” We had a few decent auditions for the werewolf part, including said assistant, but none that were particularly striking. One potential actor read for several parts, and I wanted him to read for Wolfgang. I asked the assistant to give the actor the Wolfgang sides. A short time later when the candidate took the stage, I asked him to read for the part. “Your assistant told me that I couldn’t read for Wolfgang because the part has been filled.” Scratch one assistant and any idea of a short, squat lycanthrope.

The thing about the girls [Camille and Kennerly Kitt] is that they were perceptive.

The thing about the girls [Camille and Kennerly Kitt] is that they were perceptive.

Elaine Sarah Miles was somebody I knew prior to writing the script, so when I wrote the script, I knew that I wanted her in it to sing a song.

Elaine Sarah Miles was somebody I knew prior to writing the script, so when I wrote the script, I knew that I wanted her in it to sing a song.

That takes me to this thorny problem of audience. I have gotten in a little bit of trouble with the girls over the issue of whether or not this movie is “family friendly.” I have had to do a lot of thinking about this. I have done hours and hours of entertainment that is family friendly. I’ve done Disney cartoons, I’ve done “Alvin and the Chipmunks,” “The Smurfs,” “Scooby Doo,” and “Jay Jay the Jet Plane.” But, this is not that. “Creeporia” was designed to be funny. My audience is the same audience that would turn toMonty Python and the Holy Grail or Life of Brian or Young Frankenstein.

That takes me to this thorny problem of audience. I have gotten in a little bit of trouble with the girls over the issue of whether or not this movie is “family friendly.” I have had to do a lot of thinking about this. I have done hours and hours of entertainment that is family friendly. I’ve done Disney cartoons, I’ve done “Alvin and the Chipmunks,” “The Smurfs,” “Scooby Doo,” and “Jay Jay the Jet Plane.” But, this is not that. “Creeporia” was designed to be funny. My audience is the same audience that would turn toMonty Python and the Holy Grail or Life of Brian or Young Frankenstein.

John was generous enough to let the two of us decide which scenes each of us would take for filming. However, before going into filming, we decided that we both needed to know every single line in the script – even though it is a monstrously (pun intended) large and dialog heavy script and we were splitting the role of Creeporia for most of the film. That way, either of us could easily jump into any scene and we were essentially interchangeable. There are even scenes where we’re switching off playing Creeporia!

John was generous enough to let the two of us decide which scenes each of us would take for filming. However, before going into filming, we decided that we both needed to know every single line in the script – even though it is a monstrously (pun intended) large and dialog heavy script and we were splitting the role of Creeporia for most of the film. That way, either of us could easily jump into any scene and we were essentially interchangeable. There are even scenes where we’re switching off playing Creeporia!

Bowers died, destitute and obscure, at the age of 57 in 1946, following a long illness. Although he made hundreds of animated short films, along with the live action shorts, only fifteen of his films survive. These were restored and distributed by Lobster Films in France. This indispensable collection of Bowers films is on the two-disc set Charley Bowers, The Rediscovery of an American Comic Genius.

Bowers died, destitute and obscure, at the age of 57 in 1946, following a long illness. Although he made hundreds of animated short films, along with the live action shorts, only fifteen of his films survive. These were restored and distributed by Lobster Films in France. This indispensable collection of Bowers films is on the two-disc set Charley Bowers, The Rediscovery of an American Comic Genius.

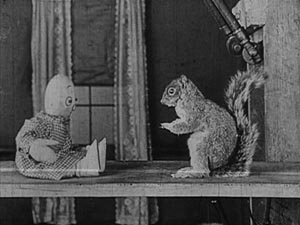

In “A Wild Roomer” Charley is an inventor yet again and stands to gain his late grandfather’s inheritance if he can come up with an invention within 48 hours. If Charley fails, the money goes to Charley’s uncle, who looks like a cross between the classic horror stars Karloff and

In “A Wild Roomer” Charley is an inventor yet again and stands to gain his late grandfather’s inheritance if he can come up with an invention within 48 hours. If Charley fails, the money goes to Charley’s uncle, who looks like a cross between the classic horror stars Karloff and  In “Now You Tell One” the Liars Club is having an annual get together. One member tells of elephants on the Capitol building, and the stop-motion animation for this looks like something akin to Ray Harryhausen to come. However, the lies lack imagination, so a senior member goes out in search for a great liar. He finds Charley trying to blow his head off in a cannon. Charley is taken back to the club. He is introduced as Bricolo, so great a liar that even the King of the Gullible would never believe him. Charley tells the club how he invented a potion that will graft together any two objects and make them grow. Pineapples and apples grow into a combined plant, as do cucumbers and squash, straws change into a hat, seeds into shoelaces, and the handle of a wheel barrel grows a Christmas tree. Charley happens upon a pretty girl with cute legs who is stressed out over a huge problem with mice. Charley grows her some cats, but like the sorcerer’s apprentice, the magic gets away from him and soon her house is overrun with cats.

In “Now You Tell One” the Liars Club is having an annual get together. One member tells of elephants on the Capitol building, and the stop-motion animation for this looks like something akin to Ray Harryhausen to come. However, the lies lack imagination, so a senior member goes out in search for a great liar. He finds Charley trying to blow his head off in a cannon. Charley is taken back to the club. He is introduced as Bricolo, so great a liar that even the King of the Gullible would never believe him. Charley tells the club how he invented a potion that will graft together any two objects and make them grow. Pineapples and apples grow into a combined plant, as do cucumbers and squash, straws change into a hat, seeds into shoelaces, and the handle of a wheel barrel grows a Christmas tree. Charley happens upon a pretty girl with cute legs who is stressed out over a huge problem with mice. Charley grows her some cats, but like the sorcerer’s apprentice, the magic gets away from him and soon her house is overrun with cats.

Quite surprisingly, The Merry Widowwas a critical and box office success for von Stroheim. The film was so successful that it was remade in 1934 by Ernst Lubitsch (as a musical, replete with the Lubitsch touch, starring Maurice Chevalier and Jeanette MacDonald) and in a best-forgotten 1952 version starring Lana Turner. Despite a studio mandated, ill-fitting happy ending, von Stroheim’s silent version is, predictably, the most bizarre. The director added much to the story, stamping it with his idiosyncratic touch and causing the film to go considerably over schedule and over budget. The previous year’s Greed had nearly bankrupted the studio and sent producer Irving Thalberg to the hospital. After The Merry Widow, von Stroheim would not direct a film for three years.

Quite surprisingly, The Merry Widowwas a critical and box office success for von Stroheim. The film was so successful that it was remade in 1934 by Ernst Lubitsch (as a musical, replete with the Lubitsch touch, starring Maurice Chevalier and Jeanette MacDonald) and in a best-forgotten 1952 version starring Lana Turner. Despite a studio mandated, ill-fitting happy ending, von Stroheim’s silent version is, predictably, the most bizarre. The director added much to the story, stamping it with his idiosyncratic touch and causing the film to go considerably over schedule and over budget. The previous year’s Greed had nearly bankrupted the studio and sent producer Irving Thalberg to the hospital. After The Merry Widow, von Stroheim would not direct a film for three years.

Comparisons to Dickens are apt, but Sjostrom’s film casts an even more complex and lugubrious milieu. The movie is based on Selma Lagerlof’s novel “Korlarlen” and, in contrast to the expressionism popular during the period, Sjostrom opts for a naturalistic setting. While The Phantom Carriage does not take the easy route of escapist fantasy for adolescent boys, that does not mean it is lacking in intensity. One scene clearly seeded

Comparisons to Dickens are apt, but Sjostrom’s film casts an even more complex and lugubrious milieu. The movie is based on Selma Lagerlof’s novel “Korlarlen” and, in contrast to the expressionism popular during the period, Sjostrom opts for a naturalistic setting. While The Phantom Carriage does not take the easy route of escapist fantasy for adolescent boys, that does not mean it is lacking in intensity. One scene clearly seeded

The Blizzard runs a complex syndicate which local law enforcement cannot penetrate. Desperate, officials send an undercover agent, Rose (Ethel Gray Terry) into Chaney’s lair. The criminal is abusive, misogynist, seedy, and initially lacking in sympathy. There is a dark, latent sexual undercurrent between the Blizzard and Rose. Only music calms the Blizzard, and Rose serves as his feet, pushing the pedals of his piano while he plays.

The Blizzard runs a complex syndicate which local law enforcement cannot penetrate. Desperate, officials send an undercover agent, Rose (Ethel Gray Terry) into Chaney’s lair. The criminal is abusive, misogynist, seedy, and initially lacking in sympathy. There is a dark, latent sexual undercurrent between the Blizzard and Rose. Only music calms the Blizzard, and Rose serves as his feet, pushing the pedals of his piano while he plays.

Trap doors, laundry shoots, secret basements and an electric chair are the props in West’s dream-world. Chaney’s Ziska is surprisingly foppish with smoking jacket, a flapper-like quellazaire, and a wayward eyebrow. Ziska wears a menacing grin at all times, making him a possible first member of a Grand Guignol Three Stooges which might include Lionel Atwill and

Trap doors, laundry shoots, secret basements and an electric chair are the props in West’s dream-world. Chaney’s Ziska is surprisingly foppish with smoking jacket, a flapper-like quellazaire, and a wayward eyebrow. Ziska wears a menacing grin at all times, making him a possible first member of a Grand Guignol Three Stooges which might include Lionel Atwill and

The world of Paul Beaumont comes crashing down when Regnard presents Beaumont’s work, as his own, to the Academy. Beaumont tries, in vain, to convince the Academy of the theft, but they take the side of the affluent Regnard as opposed to the unknown, poverty stricken Beaumont. Beaumont is belittled by his patron’s betrayal, by the mocking laughter of the academy, by the discovery of his wife’s infidelity, and, finally, by Regnard’s humiliating slap to his face. It is a slap which Beaumont now obsessively echoes in repetition every night. On the road to the discovery of his Magnificat, Paul becomes ‘HE.’

The world of Paul Beaumont comes crashing down when Regnard presents Beaumont’s work, as his own, to the Academy. Beaumont tries, in vain, to convince the Academy of the theft, but they take the side of the affluent Regnard as opposed to the unknown, poverty stricken Beaumont. Beaumont is belittled by his patron’s betrayal, by the mocking laughter of the academy, by the discovery of his wife’s infidelity, and, finally, by Regnard’s humiliating slap to his face. It is a slap which Beaumont now obsessively echoes in repetition every night. On the road to the discovery of his Magnificat, Paul becomes ‘HE.’

![HANDS OF ORLAC [1924]](http://alfredeaker.files.wordpress.com/2012/12/hands-of-orlac-1924.jpg?w=640)

Set in 17th century England, Conrad Veidt (another Jewish German refugee) is Gwynplaine , the young son of a recently executed political revolutionary nobleman. Gwynplaine is kidnapped by gypsies and, as punishment for sins of the father, he is forever maimed when his kidnappers carve a hideous grin into his face and abandon him to the elements of a violent snow storm. In a scene worthy of D.W. Griffith’sWay Down East (1920), or William Beaudine’s grimSparrows (1926), the child Gwynplaine comes upon the corpse of a frozen mother cradling her still living, blind infant daughter, Dea. Gwynplaine takes the babe in arms and finds sanctuary for them both.

Set in 17th century England, Conrad Veidt (another Jewish German refugee) is Gwynplaine , the young son of a recently executed political revolutionary nobleman. Gwynplaine is kidnapped by gypsies and, as punishment for sins of the father, he is forever maimed when his kidnappers carve a hideous grin into his face and abandon him to the elements of a violent snow storm. In a scene worthy of D.W. Griffith’sWay Down East (1920), or William Beaudine’s grimSparrows (1926), the child Gwynplaine comes upon the corpse of a frozen mother cradling her still living, blind infant daughter, Dea. Gwynplaine takes the babe in arms and finds sanctuary for them both.